Indika, out May 2 on PC and later this month on consoles, features two of my favorite things: snow and religion. After speaking with its developers and playing its demo, I was eager to check out the full game. That full game is intellectually heady and visually beautiful, though sometimes frustrating to play–perhaps intentionally so, to explore the religious conflict at the heart of its story.

Indika is a narrative game by Odd Meter, a group of Russian architects turned game developers, many of whom fled Russia when it attacked Ukraine in 2022. You control Indika, a well-meaning but unpopular nun who leaves her convent to run an errand, only to fall in with an escaped convict named Ilya. Ilya is trying to get to a religious artifact he hopes will heal his badly injured arm; Indika, looking for a resolution to her crisis of faith, accompanies him. Over the game’s six or so hours, they navigate a snowy, half industrial/half fantasy version of early 20th century Russia, solving some platforming and spatial puzzles and arguing about God.

You would imagine a nun and a convict would fall on the pro/anti religion side respectively, but their positions are actually reversed: Ilya is hugely devout, while Indika is less certain. This is in part due to a voice only Indika can hear, which seems to be the devil. Sometimes the voice, lusciously acted, narrates the action; other times it mocks Indika or challenges her faith. Odd Meter founder Dmitry Svetlow told me in November that “the game is about ‘who is God?,'” but that understanding of God is mediated through organized religion, in particular the Russian Orthodox church, and as such much of the devil’s arguments center on asking Indika to precisely rank sins or rebel against the authority of the convent. I sometimes found myself rebutting, “That’s about religion, not God” at its questions. But at the same time, the idea of a faith unfettered by structured religion–of being ”spiritual but not religious”--is a modern conception that wouldn’t have been available to Indika’s characters, even in the alternate timeline the game occurs in.

While Svetlow made clear in our interview that he doesn’t feel great about the Church, Indika is fairly even-handed in how it treats its characters’ belief or lack thereof. The devil might mock Ilya’s faith or Indika’s obedience, but the game itself doesn’t. Narratively, it’s perhaps less about God than it is about learning to explore one’s personal religious context or upbringing, and there are a lot of relatable questions and useful skills in that. I found Indika’s debate engaging, even if I didn’t always agree with its presuppositions or framing.

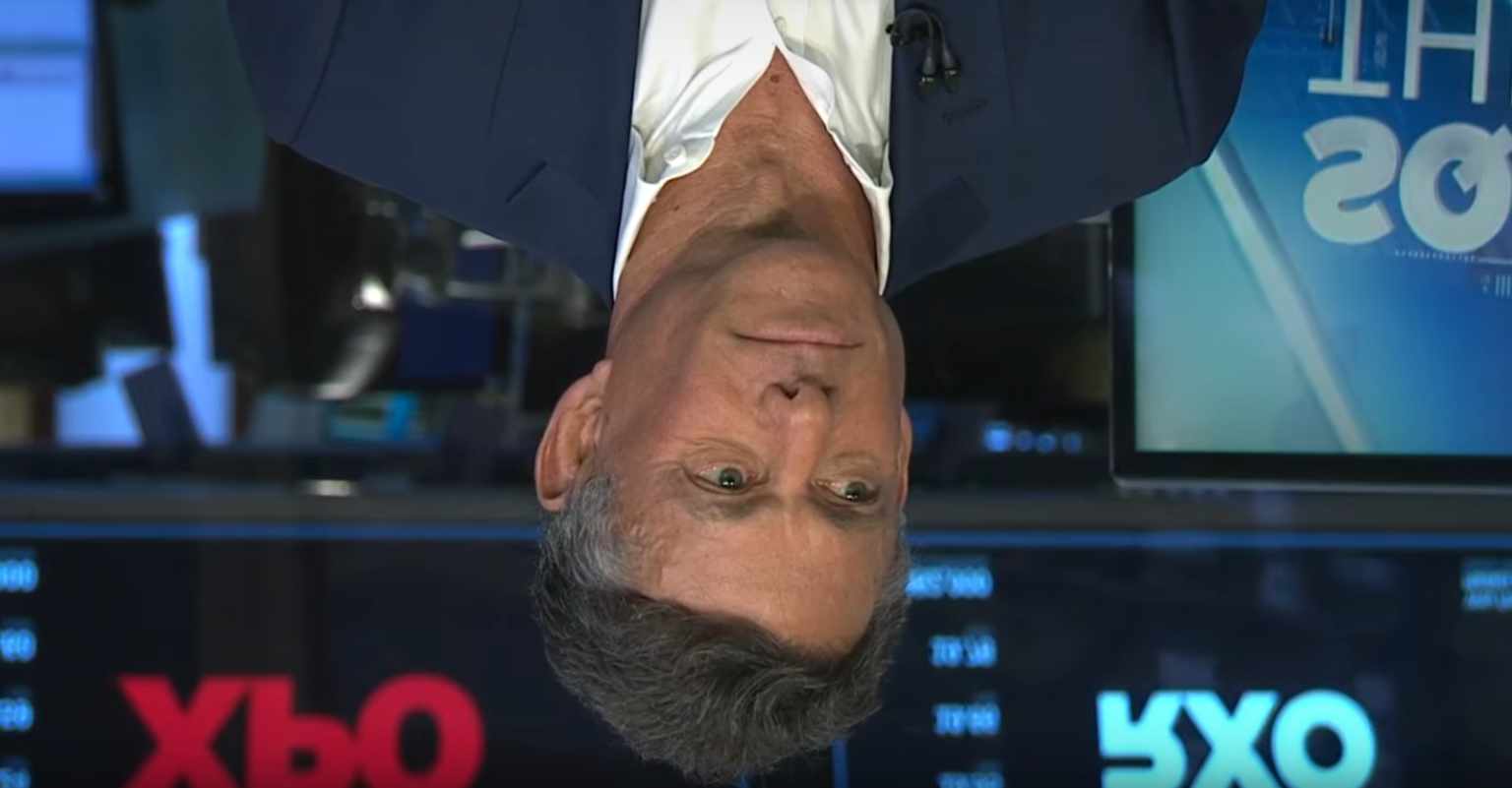

Indika’s strongest piece, as perhaps you’d expect from Odd Meter’s pedigree, is its architecture and landscape. You move through creepy towns and ruined factories that grow ever more vertiginous and dreamlike as you explore. Buildings connect at weird angles; machines and setpieces grow to nonsensical proportions so subtly that I didn’t notice until I was dodging whale-sized fish or manipulating entire city walkways. In one area, I spotted some kind of huge, inexplicable monster behind a gate; in another, dragging boxes to climb through windows, I realized I was going in an impossible loop, seeing glimpses of myself through a doorway. The game doesn’t explain or draw any attention to this, and it creates a strange, creepy tone that’s really wonderful.

Unfortunately, it sometimes doesn’t feel good to actually traverse these spaces, which you do through walking and talking, solving navigation puzzles, or through platforming. Indika doesn’t steer precisely (I played on keyboard and mouse), which could be a very appropriate design choice to tell the story of a rebellious nun. But a few sections required somewhat precise or time-based navigation that the movement didn't feel quite up to, and I was often frustrated by these parts. This feels worse in backstory sections that, while narratively interesting and animated in their own unique style, feature platforming puzzles whose logic and movement I struggled to understand. At one point in the main narrative, slogging through a multi-stage platforming puzzle, Indika groaned “Not again,” and I was right there with her.

It's possible this was just me, or was on purpose, to bolster the game’s discordant, unsettling vibes. While playing, I was reminded of a review I wrote of another religion game nearly a decade ago: Uriel’s Chasm 2, a sequel to what was back then one of the worst-reviewed games on Steam, by Rail Slave Games. That game could also be confusing and hostile to play; as I described it at the time, “It feels how the hardest parts of faith feel… It is obscure because God is obscure, because religion is obscure, because faith asks everything of you while still making no fucking sense.” Indika in some ways feels the same, some of its mechanics perhaps a physical embodiment of a particular experience of faith. If I’m correct in that interpretation, I admire the decision, even if it meant I sometimes didn’t like actually playing the game.

In some ways, I think I’m Indika’s ideal audience: I went to divinity school and have a particular interest in how religion is portrayed in art and popular culture. In another way, the game is distinctly not for me; its aggression and dissonance, much like Uriel’s Chasm 2, aren’t a big part of my own faith life, and I frequently feel disappointed by how seldom I see positive portrayals of faith that aren’t just propaganda. Despite being trans and queer, I’ve been privileged to rarely be deeply hurt by organized religion, able to explore my beliefs in accepting communities of like-minded peers and forging my own meaningful relationship to my own understanding of God unmediated by the conservative or authoritarian institutions that have harmed so many people I know. The conflict between Ilya and Indika seems to be whether someone should believe or not–an important and very real question, but one that feels a little narrow when held up against my own life or that of other religious people I know.

But that’s also one of the game’s strengths: by diving deeply into religion, instead of using it as set dressing, Indika let me bring my own beliefs and opinions to its story. My reactions to its dialogue asked me to more precisely consider what I think about God or evil or obedience. What you take away from it will surely be tempered by your own religious context or lack thereof, which is something games don’t often make space for. Even when I disagreed with Indika’s content or struggled with its gameplay, I appreciated the ways it challenged me.